here is a charming formula on Typeradio’s web-site: “Type is speech on paper. Typeradio is speech on type”. Since 2004 the archive of the internet radio channel on type and design keeps growing and counts at the moment nearly three hundred records of interviews with (type) design professionals and legends. This time Typeradio (Liza Enebeis and Donald Beekman) answers to questions from Ilya Ruderman at the type conference Serebro Nabora, September 2015, Moscow.

here is a charming formula on Typeradio’s web-site: “Type is speech on paper. Typeradio is speech on type”. Since 2004 the archive of the internet radio channel on type and design keeps growing and counts at the moment nearly three hundred records of interviews with (type) design professionals and legends. This time Typeradio (Liza Enebeis and Donald Beekman) answers to questions from Ilya Ruderman at the type conference Serebro Nabora, September 2015, Moscow.

Ilya Ruderman: Have you guys ever done an interview about Typeradio? I’m sure over the years someone must have already interviewed you. Right?

Donald Beekman: We only had an email interview. We have never actually sat down to have a chat. No video also.

Liza Enebeis: Well… we had one interview in Berlin during Designmai Festival. There were a couple of students that asked us questions but they were very along the lines of our own questions so it was a sort of a joke. They would ask our questions like “Are we religious?”, “Do we have rituals?” This happened once in Berlin and maybe once or twice over e-mail.

Liza Enebeis and Donald Beekman at the conference Serebro nabora, Moscow, 2015

Ilya: OK, let’s make it. Can you briefly explain the original idea of Typeradio? How it started? Who is involved and the whole concept because, I think, it’s not very clear to everyone.

Donald: Typeradio started when we received an invitation from Underware to join them in setting up a radio station at Typo Berlin for one time only. So, Typeradio is—Underware, the font foundry in the Hague, which consists of Akiem Helmling from Germany, Bas Jacobs from the Netherlands, and Sami Kortemäki from Finland; myself Donald Beekman, I am a graphic designer from Amsterdam; and Liza Enebeis, who is now a creative director of Studio Dumbar, but was working at another studio at the time.

The idea is that radio is a completely non-visual medium and typography is purely a visual medium. So expressing a visual medium in a non-visual way is very weird and strange. You have to think about “How does that work?”, “What’s happening? How can you explain typography if you can’t show it?” This is the basis of all the projects that we do for Typeradio, a translation from a visual thing into non-visual and then something happens. Radio is also very personal. I really like to listen to radio. What’s great about radio is that you can do something else. You can jog, you can walk, you can drive a car, whilst with video you’re stuck to the screen. It’s an old-fashioned medium in a way but also so classic, it’s timeless. I think radio will always be there. People will always listen to people talking.

Ilya: Did you have any original goal with the project?

Liza: No. It was just a one-off project. The idea was: we will go to Berlin. In Berlin you could buy radio space and we could transmit around the conference, over 500 meters.

It was real radio. We had small radios. You could buy them for a euro. We also had radio set up in the conference space. And of course we had ideas: OK, what do you do on radio? One thing was interviews or playing music. We thought that the best source at this conference would be the speakers. So why not interview the speakers about the work they do and then live-stream it in the conference? There was no podcasting back then. You could basically stream. Podcasting didn’t exist 11 years ago.

Donald: We wanted 24-hour radio. But the whole project forced us to think about how to fill eight hours of radio a day about typography. We recorded eight hours and that was repeated twice because we had to get out of the building by six or something. So it was repeated twice also to have listeners in other time zones because of the time difference.

Courtesy of Blocter

Ilya: That’s how you probably came up with the idea of starting with the same questions all the time?

Donald: The story is like this: if, for example, Erik Spiekermann is introduced, you know who he is, you know about him and about his work, but sometimes there would be a designer who is not that known and then we had no idea who we were talking to. This is kind of disrespectful to interview somebody and not know anything about him or her. So we made a scheme of twenty “yes” or “no” questions as a starting base in case we didn’t know a person. And from these answers we would continue our conversation.

Ilya: Over the years these questions changed. Now you ask fewer questions than in the beginning.

Liza: Because now they go more in depth. When we first started, we had twenty “yes” or “no” questions. And then we had a short talk. Now we have taken the “yes” or “no” questions out, we just ask certain questions from the original list and then more specific questions geared to that person. It’s more an evolution. And the other thing is that the questions are not 100% related to typography. Of course, we are interested in typography but we are more interested in the person. I think it makes a difference to the work and also how you perceive that person’s work if I know a bit more like… how you were brought up by your family. I find that interesting because it gives me a better understanding of who you are, I love your work more or I start hating your work because of who you are.

Ilya: It was always interesting to listen how differently people answer the same question. I’m wondering, did this project somehow change your personal lives, careers?

Donald: Yes, not profoundly but… What Liza and I have among other things in common is that we are very curious, we’re both very inquisitive. As soon as we meet someone we ask: What do you do? What do your parents do?

Liza: It’s not being nosy but curious.

Donald: You’re just curious and interested in people. And that didn’t change, but it gave me (and now I’m speaking for myself) the opportunity to meet more people and also people who I really look up to or admire or think they do great work. It’s fantastic – instead of just going to a conference and listening to general presentations, you have them sit down and actually have a conversation with them. So Typeradio is a kind of an excuse to talk to more people that I sort of know actually.

Liza: For me… I have a bigger respect now for typographers and type design. I started twenty years ago as a graphic designer and I didn’t know so much about the profession itself, and how much work goes into designing a typeface, and what that means. Even though as graphic designers we are the people who work directly with typography, we just don’t know what goes in it. I buy fonts and don’t download them for free. When I was a student, I remember copying all these typefaces from others. I had about a hundred floppy disks. So now I preach: buy it, don’t steal.

Ilya: Being a graphic designer, did you wish to design a typeface?

Liza: No, because I also respect how good the other people are. I like graphic design and I like it more as a whole, but I think being a typographer is a specialist area. That’s not my strength.

Ilya: I know that Donald did. I’ve heard a lecture.

Donald: No, I stick to display. I just leave the text to you guys. You actually know what you’re doing.

Ilya: Another slightly connected question. What are your favourite typefaces? What do you use by default? Which typeface are you thinking of when someone says the word “typeface”?

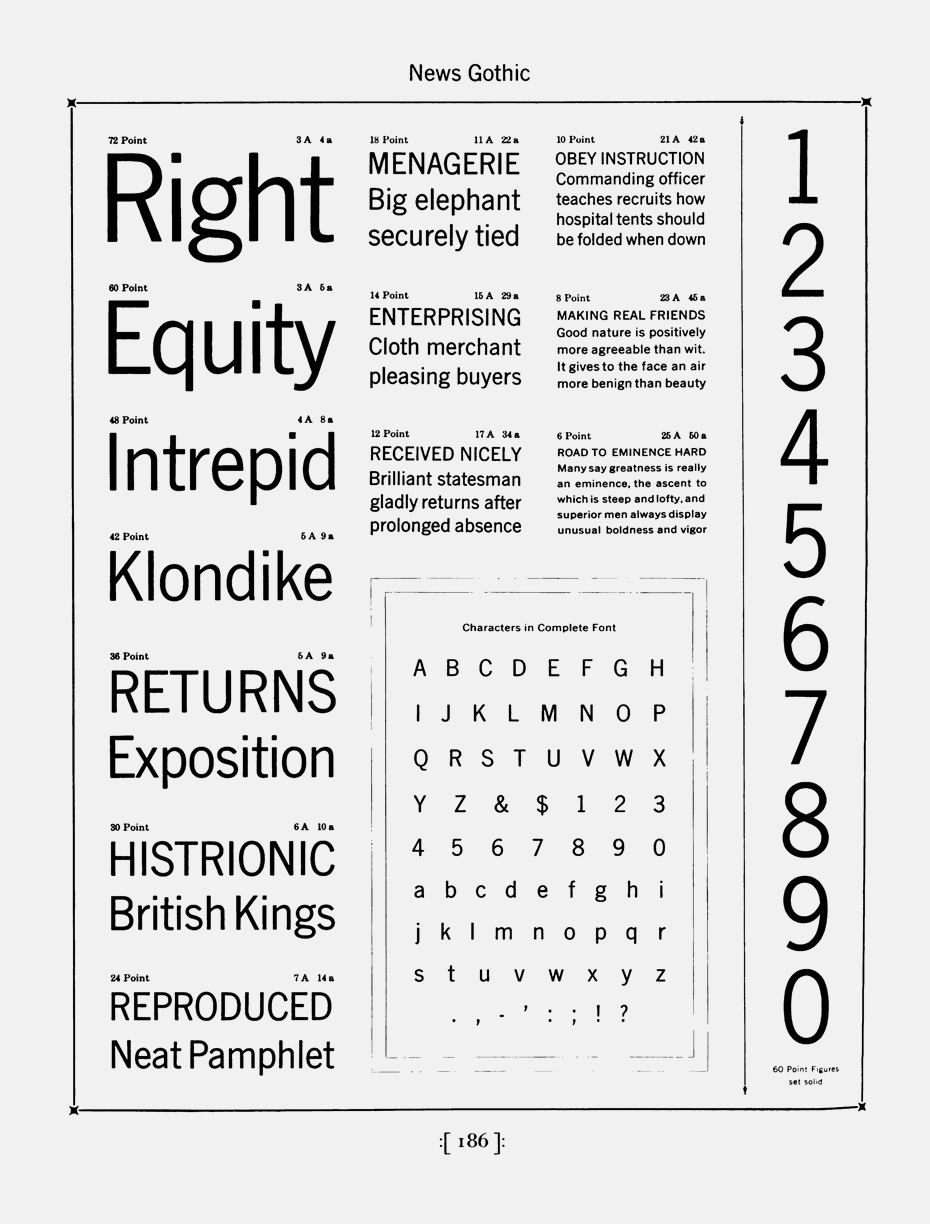

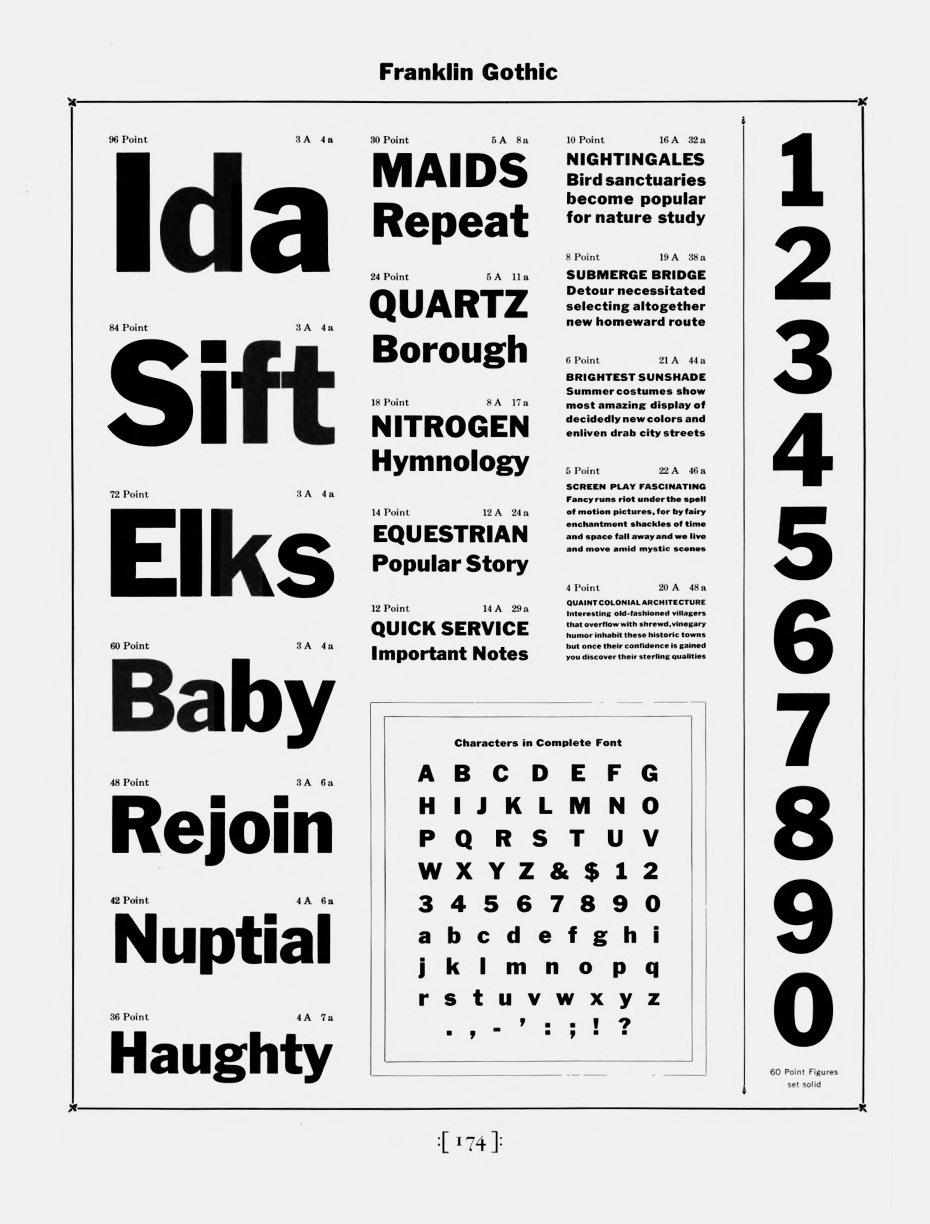

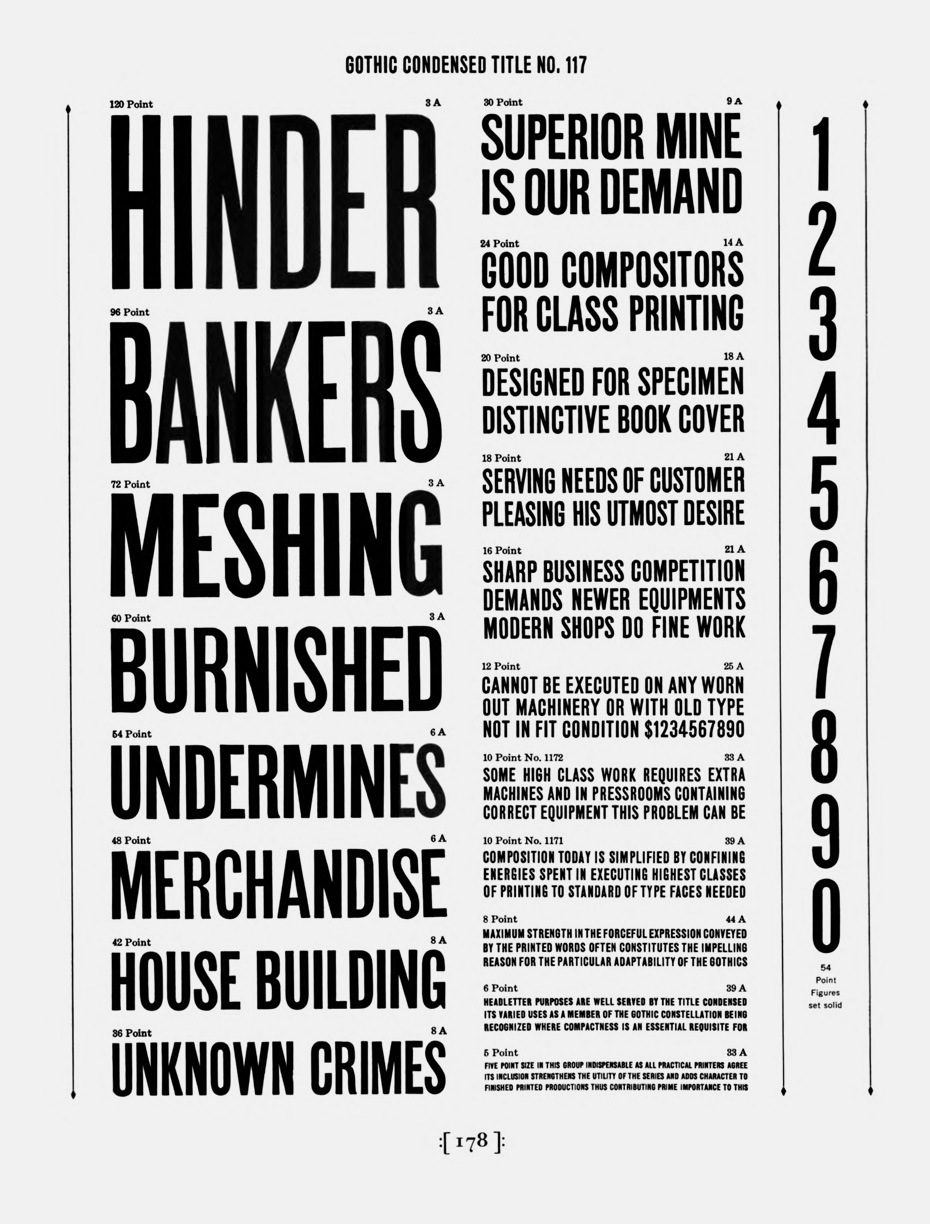

Donald: In my work in general I return to Gothics, like News Gothic, Trade Gothic, Franklin Gothic. It’s always, when I start a project and I have no idea what to use, I just start with Franklin Gothic and just see, “Oh no, this is completely wrong” and then you choose from the opposite side. When I have no idea and I need a typeface, I tend to use a sans serif and specifically American, like News Gothic.

Liza: Yeah, it’s a bit tricky. I don’t design hands-on myself because I always work with other people now.

Ilya: But you used to do this.

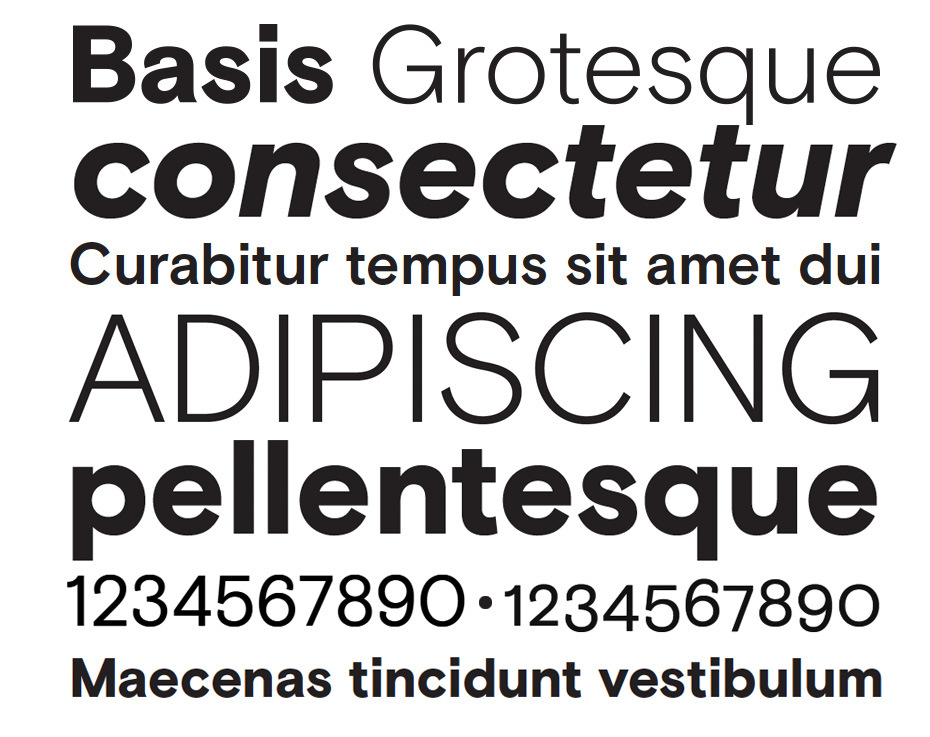

Liza: I still do it, but I always work with somebody else. My personal favourite typeface is Druk by Berton Hasebe. I did a lot of editorial design, and it really reminds me a lot of those ‘60s magazines, for example Twen or Nova, where they have these very condensed typefaces. And I really love it. You can do anything with it.

Druk is a study in extremes, featuring the narrowest, widest, and heaviest typefaces in the Commercial Type library to date. Starting from Medium and going up to Super, Druk is uncompromisingly bold. Druk was consciously designed without a normal width, nor lighter than medium weights. Berton Hasebe, the designer, wanted to avoid the compromises of forcing the typeface away from its essence for more general-purpose usage. Druk is conceived to offer new possibilities to graphic designers that other typefaces can’t. Its three widths can be mixed together for bold and expressive typographic treatments. Courtesy of Commercial Type

Ilya: Frankly, I am surprised. It’s a very original favourite.

Donald: It’s very subjective. It’s always time-based. Ask me in an hour and I’ll probably have a different answer. So it’s really what is your mood, what is coming out and what you rediscover from the past. You get there in a very indirect way.

Liza: As far as type foundries, I like the work of Grilli Type from Switzerland, and Colophon Foundry from England. These are my favourites for now, but who knows in two years’ time.

Donald: Lineto, they do fantastic work!

Ilya: And how do you choose with whom to do an interview?

Liza: It’s how good-looking they are.

Donald: And how much money they are willing to give us, of course!

Ilya: Do you vote?

Liza: No! We just say this person would be good to talk to, or other people recommend somebody.

Ilya: So you just talk to everyone.

Liza: It’s not anyone. You’re special.

Donald: You’re an exception. In general, you can say the older the designers are, the more stories and life experience and design experience they have. In general, those are the more interesting, but that’s only very general, because there are young designers who are really up and coming, do great work.

Ilya: Honestly, in general when looking at the people with whom you mainly talk—it tends to be the younger generation, rather than the older one. Why so?

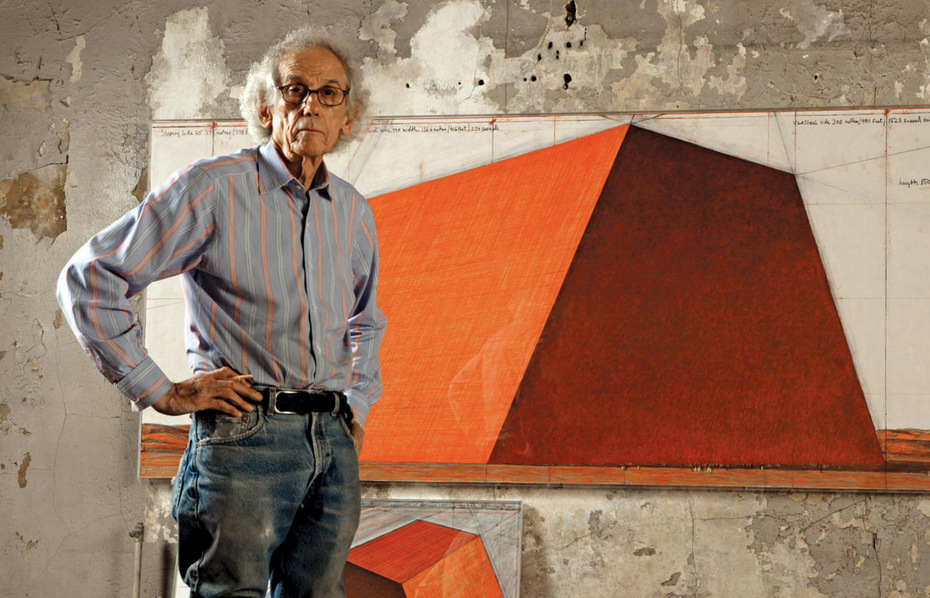

Donald: Maybe the older ones are harder to reach, harder to get in touch with. They don’t visit conferences much. As for the really famous, you have competition from radio stations and even from outside of the design world: they also want to talk to them. For instance, Christo (Christo Vladimirov Javacheff), the artist, was at the last Integrated Conference in Antwerp. He’s not a designer but we would have loved to talk to him. But with Christo you have to stand in line with the BBC, Belgium radio, Belgium television, Dutch television. So you really are the seventh in line and there’s no time for Mr. Christo to talk to us, despite the fact that everybody is very sympathetic and really trying to make it work, but it simply doesn’t happen.

Ilya: Did anyone refuse to talk with you except, as I know, Underware people?

Liza: Yeah, there are people. They just don’t really enjoy being interviewed and they say “no”.

Donald: It could be a language problem: they’re not confident enough to talk in English, for instance, or they’re shy and modest and don’t feel like it—“It doesn’t suit me to talk about my work.”

Ilya: I have a favourite question (I’m sure Liza will like this one).

Liza: Here comes the “penis” question.

Ilya: You tried to speak about that twice already… But my question is this: You have spoken with a lot of type designers. What is your honest opinion of these people? Are they normal? Are they special? Are they unique? How would you describe type designers and typographers. Are they jerks?

Liza: I think they are a very dedicated group of people. They’re not driven by money, for example. And that’s the difference from some other professions. I’m sure that people that are great at their job are never driven by money, in any profession. But particularly with type design you really have to do it for the love of what you’re doing. The commitment of these people is really unbelievable because there are very few that make their entire living at type design. They are a very committed group, maybe more so than with graphic designers—to overgeneralise.

Donald: On top of that, what they do is so abstract for people who are not in the design world or type-design world. Twenty years ago, people didn’t know what fonts were. Now they have a list OF fonts in their Windows machine. They have realised that things look different if they do them in another typeface. Comic Sans is different from Times New Roman. People know that now, so that’s like a giant leap forward since 1990.

Ilya: But it’s still a quite enigmatic profession.

Donald: If I talk to people who are not in the design world and then you explain about the distance between the letters that defines their reading experience… I mean that’s rocket science for them. It’s really like “wow!” They look at me glazed, “What the fuck are you talking about?!” “Well, it’s very important.” They sort of believe you, they seem to take your word for it, but they feel “Yeah, right! Whatever.” It’s so abstract, and and that makes for the almost weird microcosm that is the type-design world..

Liza: But it’s changing. Now I’m really happy that on the news you hear about Google redesign, for example, and it’s on every big channel: “Oh! Google changed.” I was so happy that so many people understand, “Oh, look!” They know what corporate identity is. This is already one step closer.

Ilya: And the next step will be if they know our names. Maybe.

Liza: Yeah, it’s going to take maybe another 10 years, but it’s still a step—understanding it is a part of design. So hopefully…

Ilya: I noticed that you spoke several times with several designers. You keep interviewing them.

Donald: Only Stefan Sagmeister.

Liza: No, and Indra [Kupferschmid].

Donald: Yeah, but we didn’t really do an interview with Indra at first. We just had those 20 questions. We heard 20 times “yes” or “no” from her, but we didn’t interview her. So we figured, it’s about time that we actually have a talk. Also because she’s undergone such a development in her professional life and in the typography world, so it makes sense to talk to her again.

Liza: Oh, you said about famous people: we interviewed Adrian Frutiger, but we don’t have the interview online. That’s also a nice interview that’s worth listening to. And Wim Crouwel.

Donald: Wim Crouwel is my hero. He’s my god. I looked up to this man so much and now I’m on a first-name basis with him.

I designed for this restaurant and he was having dinner there with his wife and son. And I was like, “Oh! Should I go up to him” I felt like a little boy. “He knows me now.” “Hey, Wim! What are you doing?” And he said, “Hey, Donald! How is it going? What are you doing here?” I said, “I do the design.” He said, “I love the work.” I was exhilarated for a week! Wow!

Ilya: That’s wonderful. Yeah, he’s a great designer. Who else?

Liza: Massimo Vignelli. I think it is a nice interview. It’s very funny also. His Italian accent, his flair, the way he presents his work.

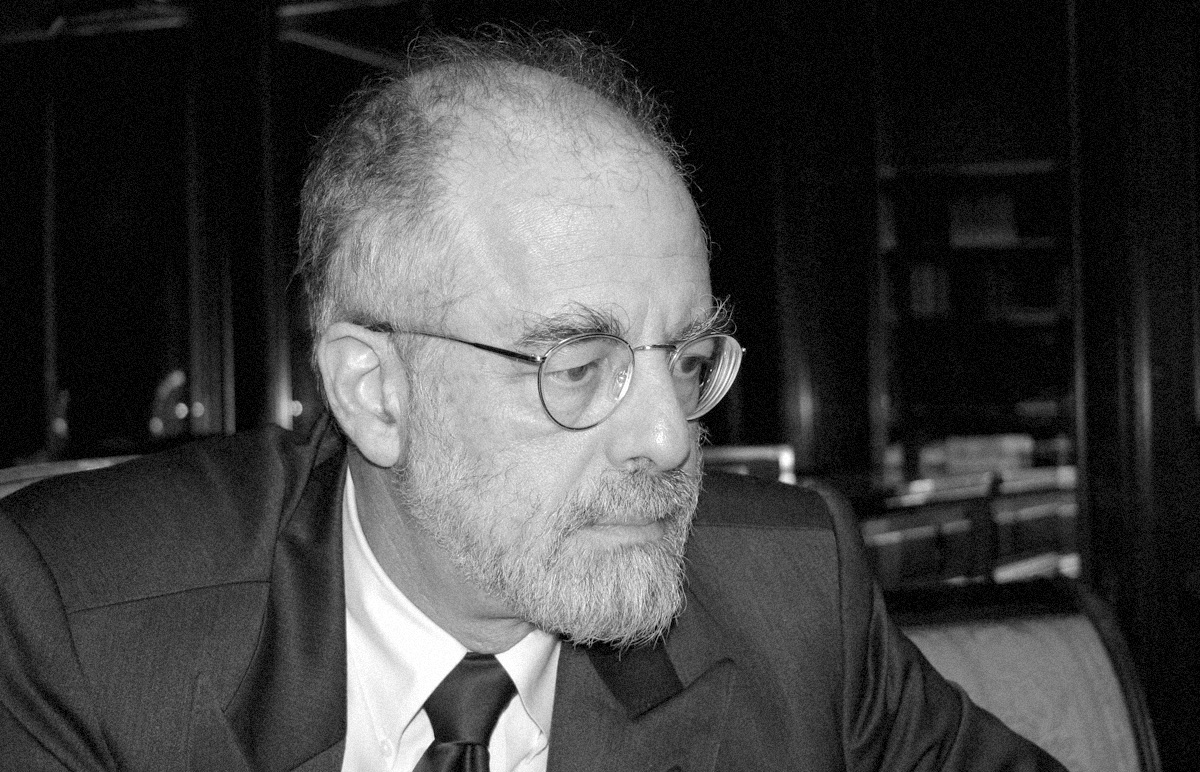

Donald: Aaron Marcus also—but that’s more because it was unexpected. We’ve never heard of the guy. We were sitting there with our eyes and ears open. Wow! We didn’t know he existed! And also Petr Van Blokland. It was also an eye-opener.

In 1967, Aaron Marcus became the world’s first graphic designer to work with computer graphics. In the 1970s, when a hard drive was the size of a refrigerator, he was already designing virtual environments and navigation through information spaces. He quickly identified the user interface as a major factor in implementing the user experience of computer-based products and services. The untapped potential to turn information into knowledge motivated him to become a researcher in computer graphics and a pioneer user-interface designer by 1969. After teaching for more than a decade, he founded the first independent, computer-based graphic design firm in the world in 1982.

Official site. Photo by Ilya Schurov, Computerra Weekly, 2008.

I should listen to it again, but in retrospect I think that he answered every question at first with “Well, that depends”, “It depends what you define as…” It made me think you should always question the tools that you work with, the programmes that you work with. The questions are being asked—well, it depends what the parameters are, what is the space that you move in. He turns everything upside down. After that conversation, I was sort of “Yeah…” You start to doubt everything that you do, but that’s in a good way, reassess everything that you’ve done. Why do I use this programme? Why it is occurring like this? Everything is like “Why? Why do you do that?” That was very interesting.

Ilya: That’s the general impression from Petr. He is quite unique in this.

Liza: There are also interviews that are really difficult in the sense that somebody doesn’t feel comfortable talking, or as a person is very closed. It’s like “Yes-no” and then you sit there wondering what to ask next.

Ilya: I wrote the question down but have not decided whether I should ask it or not: are you considering stopping the project in the future?

Liza: If there’s the end of typography—maybe.