mong many attempts to reform the Cyrillic alphabet one of the earliest is the essay entitled «Новые усовершенствованные литеры для русского алфавита» (“New, Improved Letters for the Russian Alphabet”), anonymously published in 1833 by the printing house of Auguste-René Semen in Moscow. It proposed a scheme for transitioning the Russian language to a mostly Latin writing system with some Cyrillic letters, keeping their number to the minimum (e.g. the similar-sounding e, ѣ and э were discarded in favour of the e with various diacritics).

mong many attempts to reform the Cyrillic alphabet one of the earliest is the essay entitled «Новые усовершенствованные литеры для русского алфавита» (“New, Improved Letters for the Russian Alphabet”), anonymously published in 1833 by the printing house of Auguste-René Semen in Moscow. It proposed a scheme for transitioning the Russian language to a mostly Latin writing system with some Cyrillic letters, keeping their number to the minimum (e.g. the similar-sounding e, ѣ and э were discarded in favour of the e with various diacritics).

In the 1920s, an official commission was established by the Soviet government to develop a proposal on the latinisation of the Russian language and creation of a new “unified” alphabet for the Soviet republics. This proposal was never implemented, falling the victim of the changing ideological climate. In Stalin’s 1930s Russia the Latin alphabet became politicised, thought of as “a reflection of the ideology of the class and society that created it,” and therefore suspect. The aborted project was relatively timid, compared to others. To cite one example, Eric Gill was far more radical than the Soviet linguists. A chapter “But Why Lettering?” appeared in the second edition of his famous Essay on Typography, in which Gill suggested replacing Latin letters with shorthand to streamline the process of writing to the speed of machine production. In view of the fact that Gill considered the dehumanising industrialisation an obvious evil, this suggestion was made somewhat tongue-in-cheek. Herbert Bayer at Bauhaus, who rethought Latin graphemes, as well as Jan Tschichold, and other typographers and artists, worked on the “universal alphabet” around the same time. Tschichold further endeavoured to simplify a number of complex phonetic combinations in the German language using Bayer’s alphabet as a basis.

The originality of the Telingater essay published below lies in the fact that the author does not simply propose a switch the Russian language from the Cyrillic writing system to Latin, but tries to build a universal alphabet for a number of languages. His attempt to organise the alphabet graphically in terms of the similarity of letterforms is particularly noteworthy, though he (like his predecessor, the author of the 1833 New, Improved Letters for the Russian Alphabet) recognises the need for additional diacritical marks. Another important feature of Telingater’s paper is the time when it was released, the Khrushchev Thaw, when after decades of Stalinist dictatorship the tightly fettered culture started to gradually return many valuable and interesting modernist 1920s projects from oblivion. This applied to all areas of art, and typography was no exception.—The editors

In 1964, Solomon Telingater, Soviet book artist, prominent book and type designer was among the guests of honour at a symposium to mark the bicentenary of the Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst (Academy of Visual Arts), Leipzig. According to Vadim Lazursky, Telingater’s paper “Standardisation of Alphabetic Graphemes” was given a hostile reception by Jan Tschichold, who also spoke in the Academy’s auditorium on that day. This is not surprising, since by the mid-1960s the once radical typographer, propagator of Bauhaus ideas and author of the acclaimed Die neue Typographie (1928), advocated the exact thing that he rebelled against in his youth—the Renaissance traditions in printing, incunabula models in book design and the classical canons of the book. The thrust of Solomon Telingater’s “unified alphabet” theory was too utopian and did not sit well with Tschichold, who by that time had forsaken the bold ideas of his youth. In fairness, we should add that Telingater (no less of a revolutionary in 1920s typography) was also furious about Tschichold’s report “The Importance of Tradition in Typography” and branded him a “renegade”. From left to right: Jan Tschichold, Solomon Telingater, Andrei Goncharov (1903–1979, prominent Soviet graphic designer, book artist, student of Vladimir Favorsky). Leipzig, Old Town Hall, 1964.

It is difficult for me to shed the impression that our various alphabets have, during their historical development, forfeited their original advantages and have complicated their wide-spread utilisation instead of retaining and further developing those advantages. As a result, we are faced today with the question—or challenge—of unification and simplification of the graphemes of national alphabets which are based on the Roman and the Greek alphabets. The classic foundation of these national alphabets was constructed in such a way that each grapheme was the equivalent of a definite phoneme; or, expressed differently, that each letter denoted a sound.

It is not necessary here to analyze deeply the reasons for this historical development nor the fact that in our contemporary alphabets different relationships between graphemic and phonetic systems have crystallized themselves; but it should be emphasized that the complicated graphemic visualization of some sounds (eaux, a, ch, oi, etc.), the existence of silent letters, or the deviations in the pronunciation of letters in relation to their alphabetic sound value constitutes a certain regress when compared to the simple and clear readability of the Roman and Greek alphabets. There seems to be a certain defect in the historical development of divers sound values of the same letterform (e.g., P-R in the Russian, and P-P in the Latin language). We are faced here with a basically different pronunciation, not merely with a dialectal distinction. One could elaborate on this complex of questions: different phonetic values of the same letter, double recording of the same sound, wrong rhythmic direction in the recording of the graphemes, etc.

In this connection a utilitarian and perhaps not too naive a question should be raised: could man not find ways to correct these historical deficiencies? A radical solution could be the unification of the graphemic systems of those alphabets which are derived from the Roman and the Greek alphabets. Furthermore, the unified, standardised graphemes should be made mandatory for all of the alphabets within the Roman-Greek and Greek-Cyrillic group. The system of diacritical marks should be equally standardised in principle.

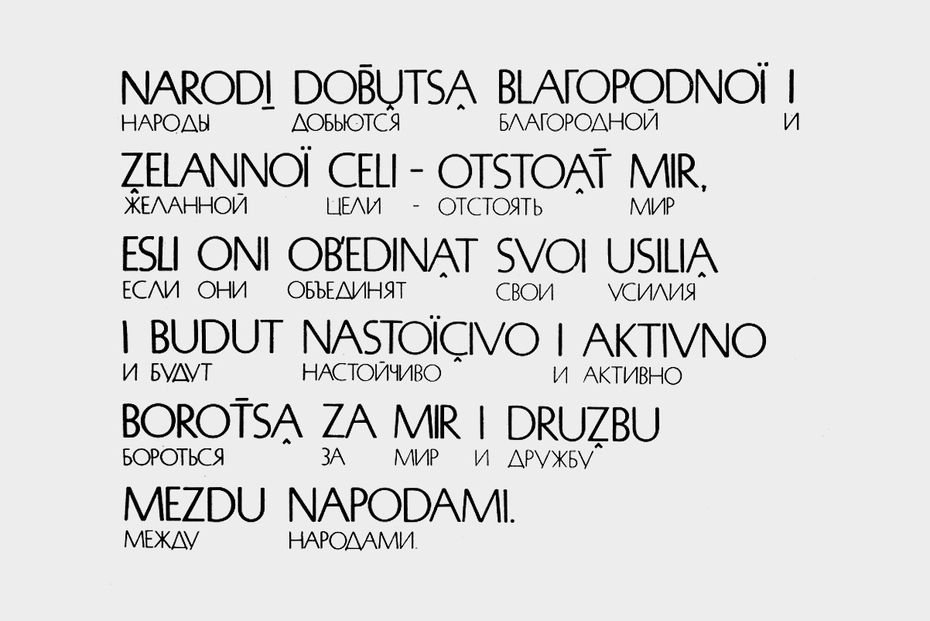

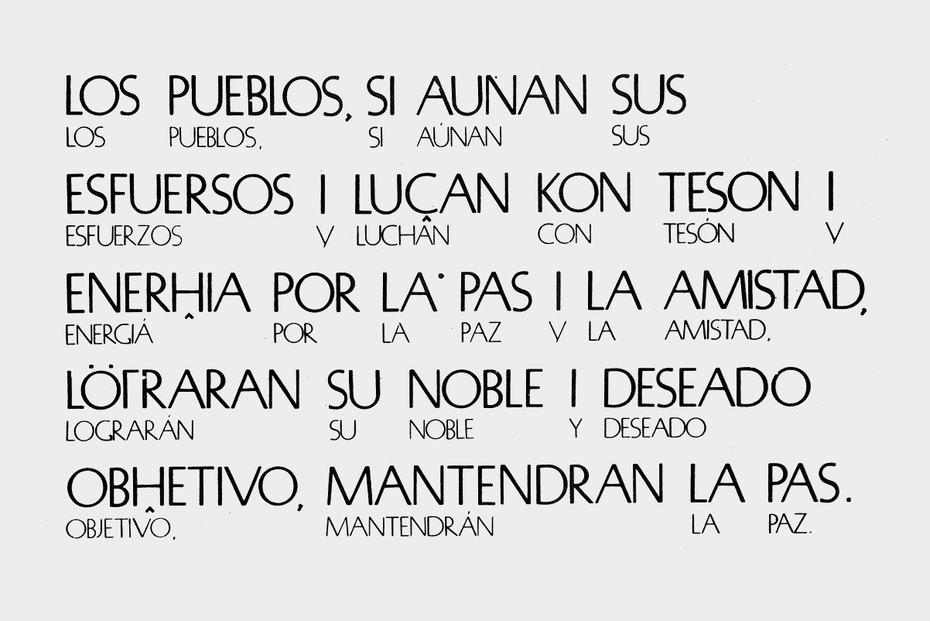

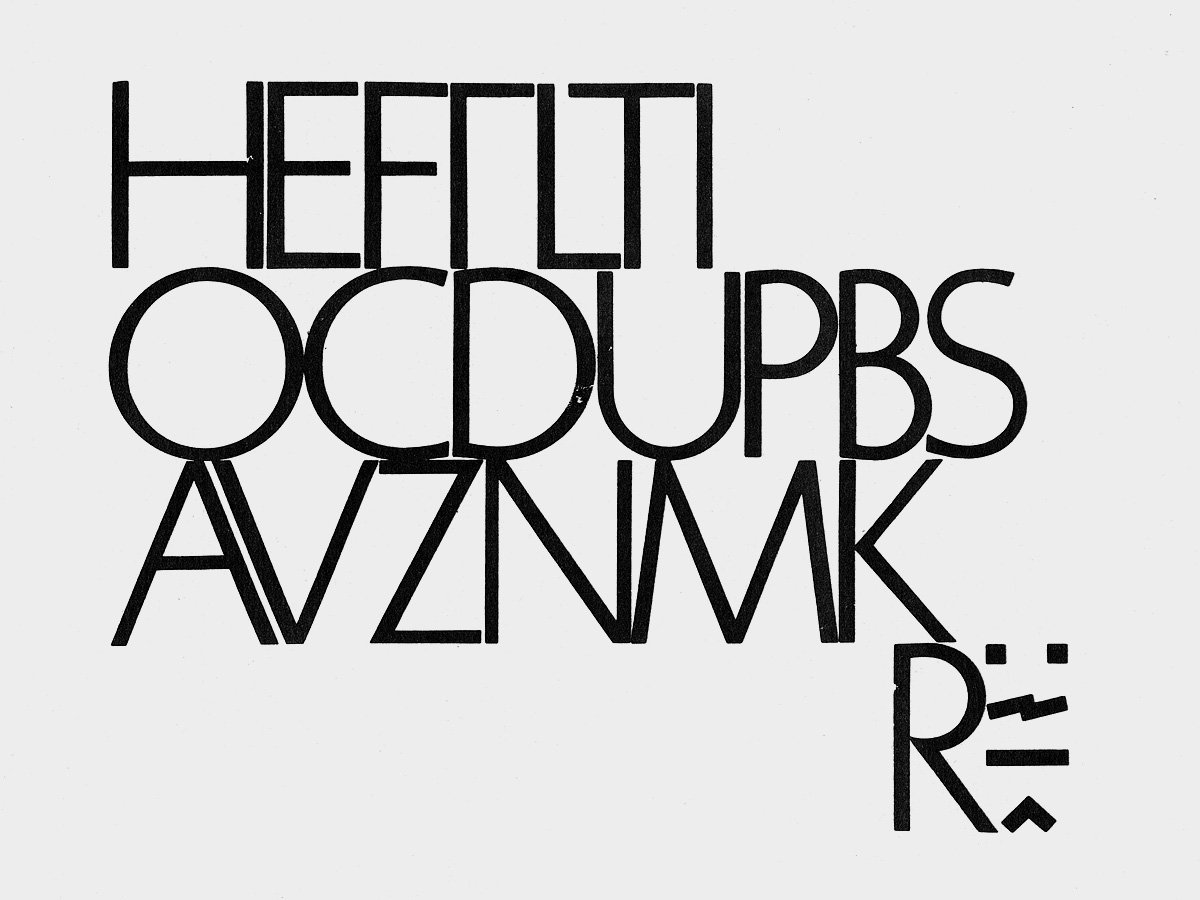

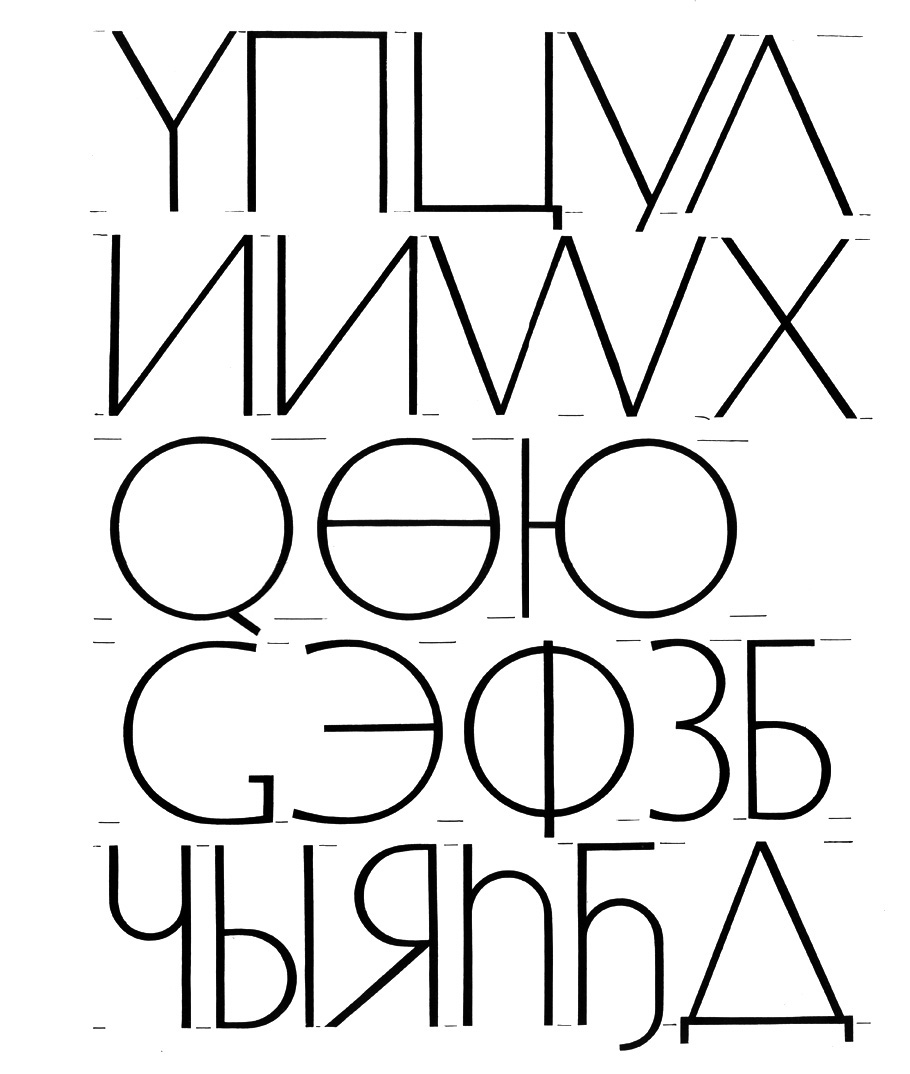

The table of graphemes presented here is merely an initial step requiring further discussion and development. At the same time I am also recommending a new arrangement of the graphemes within the alphabet, which is dictated by the character of their graphic forms. In this way, one must assume, a certain practical sense of logic would express itself in the arrangement of the alphabet (the precision of the system of graphic construction replaces the historical sequence which lacks any systematisation).

Graphemes as proposed by the author and arranged on the basis of the character of their graphic forms. 1965.

There is no doubt that the implementation of this idea would, in all practicality, stretch over several generations. Even in the normal process of development, past historical deficiencies would have to be eliminated. Many difficulties would undoubtedly arise; within every language special problems would have to be coped with.

It is certain, however, that the progressive development of history and of mankind is closely related to the peaceful coexistence and the economic and cultural relationships among nations. International tele-communication and travel which promote such relationships are developing at an accelerated pace. Nobody can deny that the standardisation of the alphabet could be of eminent importance in this respect. The rising development of science and technology (faster than we realize) is elevating humanity to a level at which the multitude of different alphabets should be considered a serious impediment for the future progress of civilization on our planet.

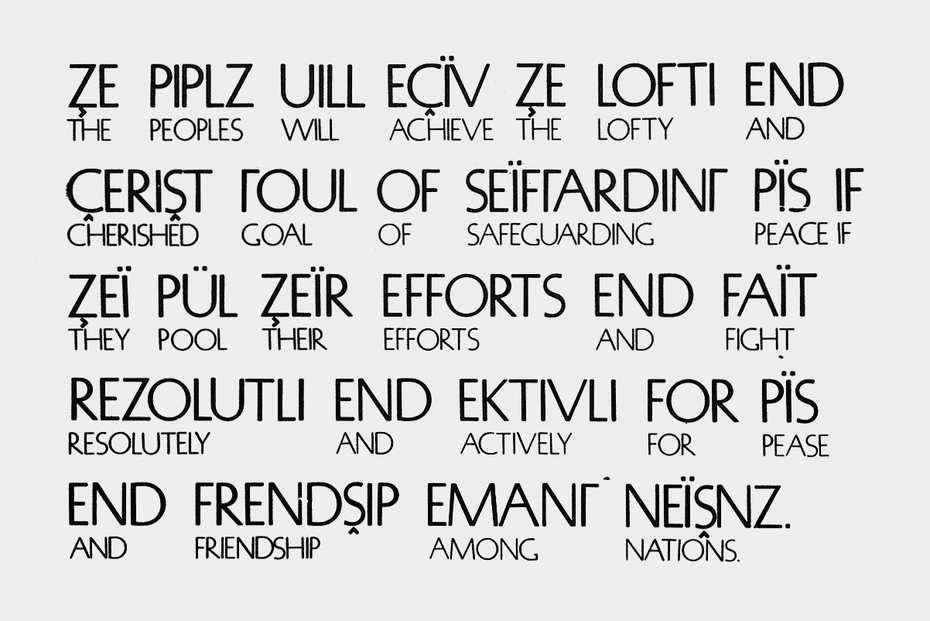

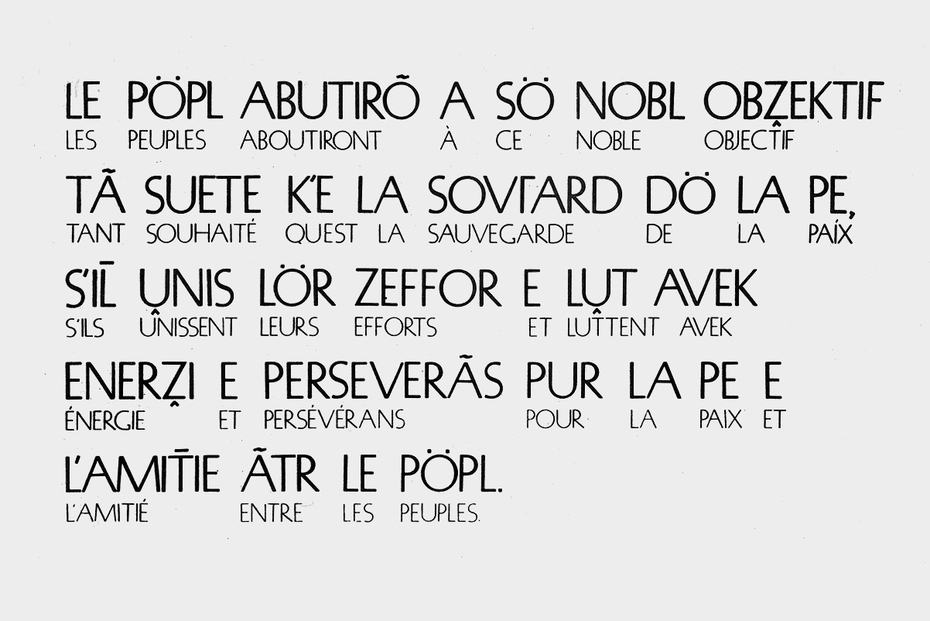

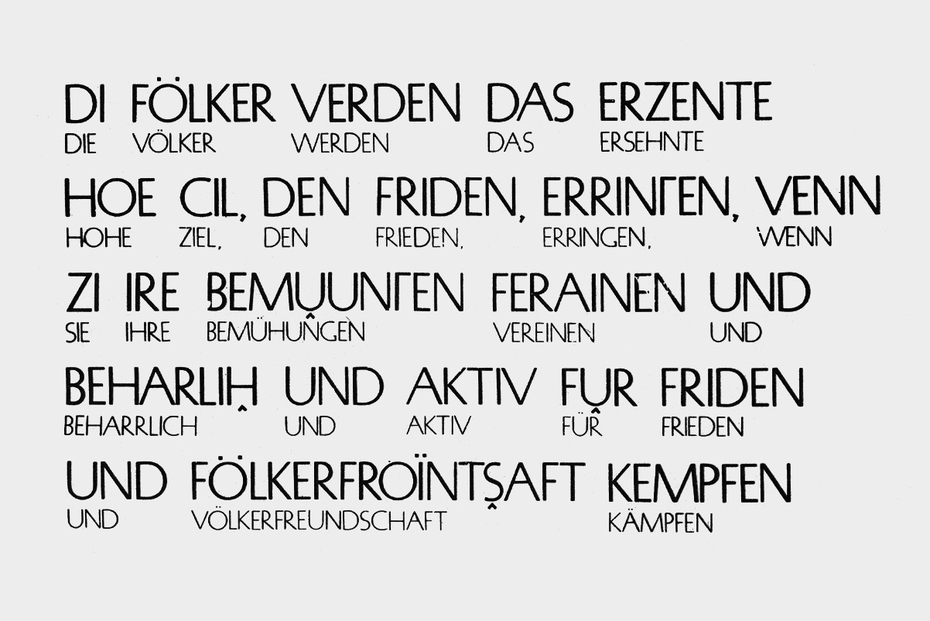

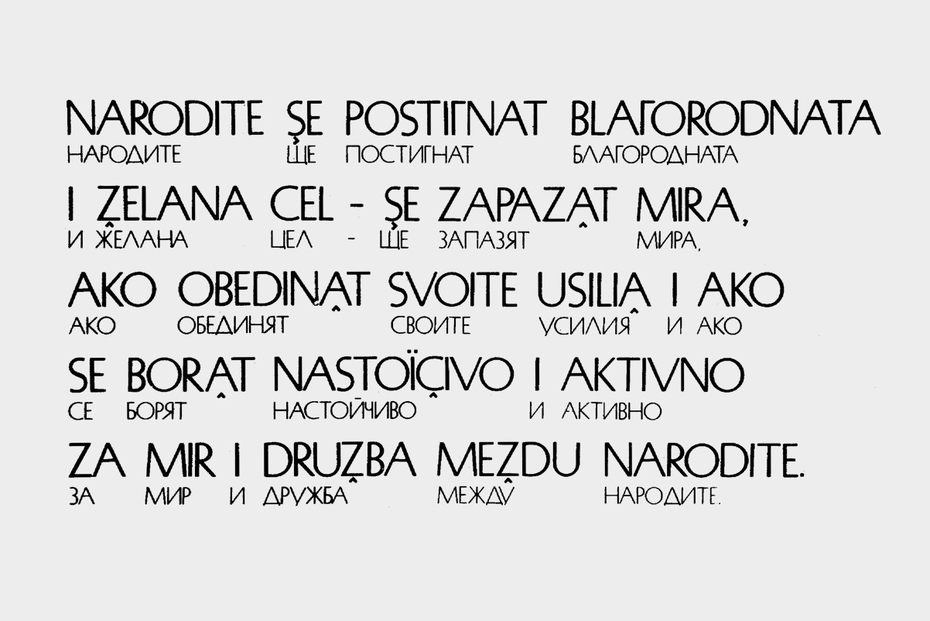

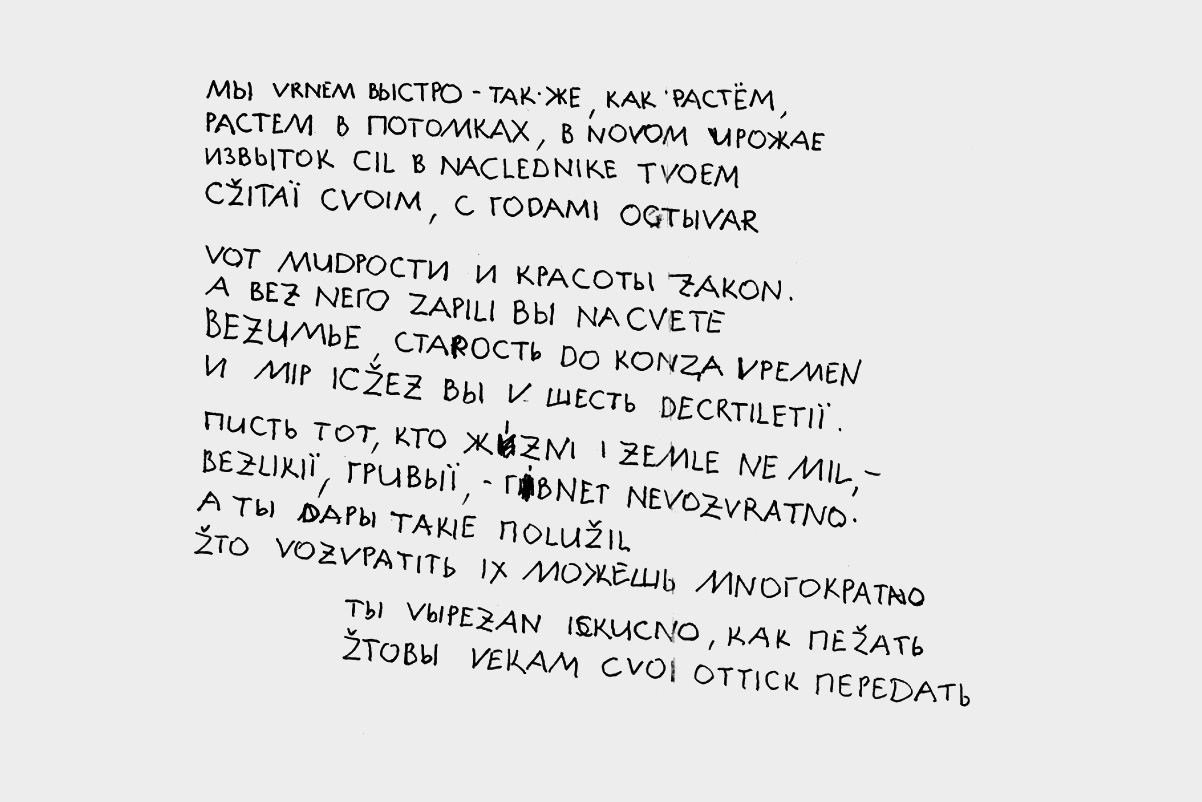

Author’s draft of a text written with the unified alphabet. 1965.

The practical implementation of this promising task would undoubtedly have to be performed in tactical stages. These stages might include: elimination of the archaisms in our alphabets and of the silent, unpronounced letters; improvement of the diacritical marking system; standardisation of individual letters with national alphabets, etc. A general solution based on territorial or language areas would have to be arrived at after international discussions have taken place.

It is interesting to note that the standardisation of alphabetic graphemes on an equal phonetic basis could result in a reduction of text lengths from 20% to 25% in some languages, especially French and English. In this connection, it should be pointed out that this proposal has nothing to do with the ideas of the Esperantists; it confines itself to a reform of alphabetic graphemes and in no way attempts to alter the various national languages.

Sketches of several characters in Solomon Telingater’s unified alphabet—characters that have a unique structure (Y, П, Ц, У, Л, И, Х, Q, О, etc.), the structure of two single graphemes (Ф, W) and of two different graphemes (Б, Я, Ю). 1965.

Phonetists always emphasise the fact that the original forms of the alphabets utilised by us were not derived from a phonetic basis but from a graphic, pictorial one. The signs of the phonetic script had their origins in the hieroglyphs. If one could incorporate the subtleties of human speech and the phonetic richness of our language into the creation of a corresponding alphabet, a multitude of new and useful graphemes and combinations would be the result. But even then, many of the delicacies of phonetic combinations and of other language finesses would be impossible to record. We must bear in mind that any standardisation of alphabets should lead to a minimum of graphemes, and all of the general phonetic variations must be expressed through the diacritical system.

In the Soviet Union the standardisation of the alphabet or the introduction of a unified alphabet could be relatively easy, since one is familiar here with different alphabets. In our country, almost the entire young generation knows the Latin alphabet. One can imagine, however, that the practical implementation of an alphabetic standardisation could cause many difficulties in individual languages. In French, for instance, we use the letter s for the plural form. If we let ourselves be guided by the principle that a sound equals a letter, all silent letters should not be written. What about the formation of the French plural in that case? Spoken French may help us here. It must be assumed that a Frenchman—on the basis of the context of the sentence—can understand very well whether a word is used in its singular or plural form, in spite of the fact that the s is unpronounced.

Similar examples can also be found in other languages; if we are to hope for solutions to these problems, we must look to the philologists for guidance.

The examples shown here are, by no means, designed as final solutions to the questions I have raised. They are merely to illustrate the basic idea of my general proposal.

In conclusion, let me suggest that we admit, first of all, that the present form of many national alphabets can on all probability be improved. Once we agree on that, all research people whose work impinges on alphabetic studies would be called upon to participate actively in its continued development and modification on an international cooperative basis.

In the 1930s, Soviet type designer Faik Tagirov introduced a term denoting the graphic expression of a “phoneme” – the skeleton of a letter devoid of any stylistic properties. According to Tagirov, there were three aspects of the phoneme’s graphical appearance. The first represents the graphic expression of a phoneme in upper and lower case, while the second one denotes the graphic expression of a phoneme using different faces, including handwriting styles. Finally, the third appearance signifies the graphic expression of a phoneme using different styles within one type family (bold, regular, italic, etc.). See also Solomon Telingater’s “Über das Grafem des Alphabets” in Typografie, 1965/1, pp. 21-23.